Sustainable Fashion and the Rights of Indigenous Workers

Respecting Traditional Knowledge and Cultural Heritage

Respecting Traditional Ecological Knowledge

For countless generations, indigenous and local communities have cultivated a profound understanding of their environments. This wisdom, known as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), represents more than just practical survival skills - it embodies a sacred relationship between people and nature. What makes TEK invaluable is how it interweaves empirical observations with cultural values, creating sustainable practices that have stood the test of time. Unlike modern scientific approaches that often compartmentalize nature, TEK views ecosystems as interconnected webs where every element has purpose and meaning.

These knowledge systems don't merely describe the environment; they reflect a philosophy of coexistence. The spiritual dimensions of TEK foster a deep sense of responsibility toward the land, ensuring that conservation becomes a cultural imperative rather than just an environmental strategy.

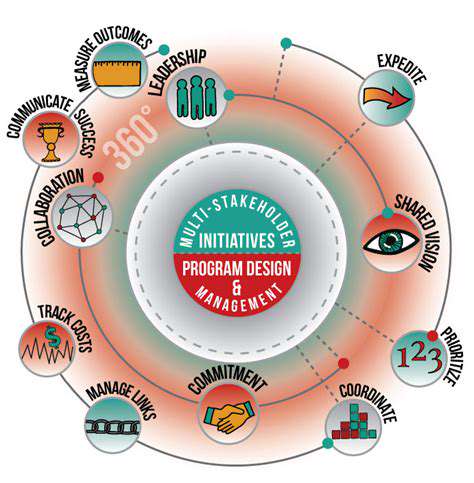

The Importance of Collaboration

Imagine combining centuries-old wisdom with cutting-edge science. When indigenous knowledge holders and researchers work together, remarkable solutions emerge. This partnership works best when built on mutual respect - where scientists value traditional insights as much as lab data, and communities feel their knowledge is honored, not exploited. Successful collaborations often start small, focusing on specific conservation challenges where both systems can complement each other.

Key to this process is ensuring indigenous communities lead these efforts rather than just participate in them. Too often, traditional knowledge gets extracted without proper context or benefit to its holders. True collaboration means establishing fair protocols for knowledge sharing and recognizing intellectual property rights.

Cultural Significance of TEK

TEK represents more than environmental practices - it's the living memory of cultures. Each technique for water management or plant cultivation carries stories, ceremonies, and identities. When we protect these knowledge systems, we're not just conserving ecosystems; we're preserving irreplaceable cultural heritage that offers alternative ways of understanding our world.

For indigenous youth, this knowledge provides a vital connection to their ancestry. As globalization homogenizes cultures, TEK serves as both an anchor to tradition and a compass for sustainable living in modern contexts.

Sustainable Resource Management Practices

Consider the sophisticated forest management techniques developed over centuries - from controlled burns that prevent catastrophic wildfires to selective harvesting that maintains biodiversity. These aren't primitive methods, but rather time-tested systems that modern ecology is only beginning to appreciate. What appears simple often reflects deep ecological understanding passed through generations.

The brilliance of these systems lies in their adaptability. Indigenous communities continuously refine their practices based on environmental changes, demonstrating a dynamic approach to sustainability that static regulations often lack.

The Role of Indigenous Guardianship

Across the globe, indigenous territories contain the healthiest ecosystems remaining on Earth. This isn't coincidence - it's the result of active, knowledgeable stewardship. Indigenous guardians serve as the memory of the land, noticing subtle changes that indicate ecological shifts long before instruments detect them. Their presence deters illegal activities while maintaining cultural connections to the landscape.

Supporting these guardianship programs doesn't just benefit the environment - it strengthens communities by validating their role as protectors and creating sustainable local livelihoods connected to traditional values.

Addressing Knowledge Gaps and Misunderstandings

The gap between western science and TEK often stems from fundamental differences in worldview. While science seeks universal laws, TEK embraces context-specific solutions. Bridging this divide requires more than translation - it demands a paradigm shift where we value different ways of knowing equally. Educational systems play a crucial role here, teaching both indigenous and scientific perspectives.

Researchers must approach TEK with humility, recognizing that some knowledge may be sacred or protected. Building trust takes time, but the ecological insights gained make the process invaluable.

Empowering Indigenous Communities

Genuine respect for TEK ultimately means supporting indigenous self-determination. This goes beyond consultation to actual decision-making power over ancestral lands. When communities control their resources, they implement conservation strategies aligned with both ecological and cultural priorities. Legal recognition of land rights forms the foundation, but ongoing support for governance capacity ensures long-term success.

This empowerment creates ripple effects - strengthening cultural identity, improving community well-being, and providing models of sustainability that the wider world desperately needs. The future of environmental conservation may well depend on how seriously we take these traditional knowledge systems today.