The Impact of Textile Waste on Ocean Pollution and Marine Life: New Research

The Ubiquitous Presence of Microplastics

Microplastics—those tiny plastic fragments smaller than a sesame seed—have infiltrated nearly every corner of our world. They lurk in Arctic ice, swirl in ocean currents, and even settle on remote mountaintops. What makes these particles especially alarming is their ability to bypass traditional filtration systems, entering our food chain with consequences we're only beginning to comprehend. Their persistence in the environment creates a pollution time bomb that future generations will inherit.

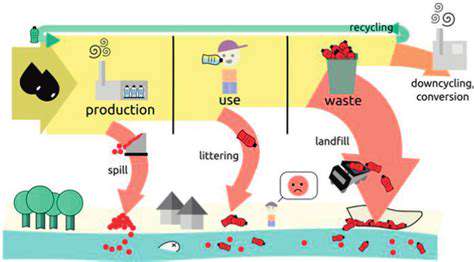

Sources and Pathways of Microplastic Contamination

Our clothing choices unknowingly contribute to this crisis. Every time we wash synthetic fabrics like polyester or nylon, thousands of microfibers break loose. These fibers flow through wastewater systems, with many slipping past treatment plants into rivers and oceans. Industrial processes add to the problem, grinding down larger plastic items into microscopic fragments. Urban runoff carries these particles through storm drains, while wind transports them across continents—creating contamination pathways we're struggling to map, let alone control.

Impact on Marine Ecosystems

The ocean bears the brunt of this invisible invasion. Filter feeders like mussels and krill mistake microplastics for food, filling their digestive systems with indigestible particles. Scientists recently discovered that coral polyps—the architects of reef ecosystems—will consume microplastics instead of their normal diet. This dietary deception weakens entire reef systems, threatening the quarter of marine species that depend on coral habitats. As these particles move up the food chain, they concentrate toxins in larger predators—including the fish that end up on our dinner plates.

Effects on Human Health

Researchers are sounding alarms about potential health impacts, though many questions remain. Early studies suggest microplastics might trigger inflammatory responses when they lodge in human tissues. The chemicals leaching from these particles—plasticizers, flame retardants, and other additives—could disrupt endocrine systems. Most concerning is the discovery of microplastics in human placentas and bloodstreams, suggesting these particles breach even our most protective biological barriers. While definitive health conclusions await further study, the precautionary principle suggests we should act now.

Mitigation and Remediation Strategies

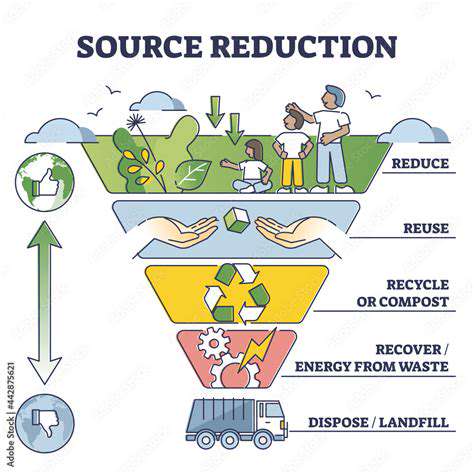

Innovative solutions are emerging across multiple fronts. Washing machine manufacturers now offer models with built-in microfiber filters, capturing up to 90% of shed fibers. Some clothing brands incorporate smoother fiber constructions that resist shedding, while scientists develop magnetic nanocoils to extract microplastics from water. Perhaps most promising are biodegradable alternatives to synthetic fibers—materials engineered to break down harmlessly in marine environments. These technological advances must be paired with policy measures like extended producer responsibility laws to create systemic change.

Future Research and Policy Implications

The scientific community urges accelerated research into microplastic impacts and solutions. We need better detection methods to track these particles through ecosystems, and longitudinal studies to understand long-term health effects. Policymakers face the challenge of creating international standards for microplastic emissions—a complex task given the global nature of both the problem and the textile industry. Some nations are leading the way; France now requires all new washing machines to include microfiber filters by 2025. Such regulatory actions, combined with consumer education, could significantly reduce microplastic pollution within a decade.

The Perilous Journey of Textile Waste to the Sea

The Unseen Toll of Microfibers

What disappears down our drains creates an environmental nightmare miles away. A single load of laundry can release hundreds of thousands of microfibers—so small they evade treatment plants, yet numerous enough to form synthetic sediment on ocean floors. Marine biologists find these fibers everywhere from surface waters to deep-sea trenches, often outnumbering natural particles. Recent autopsies of filter-feeding whales reveal stomachs packed with synthetic fibers, illustrating how thoroughly we've contaminated marine food webs.

The Disastrous Downstream Effects

Textile waste follows water's path with devastating efficiency. Discarded clothing snags on river rocks, forming artificial reefs that alter water flow and trap other debris. In ocean gyres, synthetic garments slowly disintegrate into a toxic confetti that marine animals mistake for food. The most heartbreaking casualties are sea turtles that ingest floating textile fragments, their digestive systems blocked by colorful rags mistaken for jellyfish. On some remote Pacific islands, researchers find more clothing fibers in beach sand than natural sediment—a sobering testament to fashion's global footprint.

The Role of Washing Machines and Laundry Detergents

Our laundry routines unwittingly feed this crisis. Standard washing machines act as microfiber factories, with agitation forces tearing thousands of fibers loose with each cycle. Certain detergent formulations exacerbate the problem—surfactants that make clothes cleaner also help fibers separate and disperse. Front-loading washers prove slightly gentler than top-loaders, while washing full loads with cold water reduces fiber loss by nearly 30%. Simple behavioral changes, combined with aftermarket filter installations, could prevent tons of microfiber pollution annually.

The Global Scale of the Problem

Fast fashion's exponential growth turned clothing into disposable commodities. The average garment now sees just seven wears before disposal—a shocking decline from previous generations' standards. This wear-it-once culture floods developing nations with secondhand clothing they can't possibly use, creating mountainous textile dumps that leach fibers into waterways. The problem transcends borders; microfibers from Asian textile factories drift on atmospheric currents to settle on Western glaciers, demonstrating pollution's relentless global circulation.

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

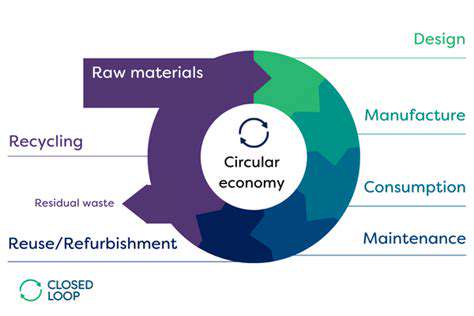

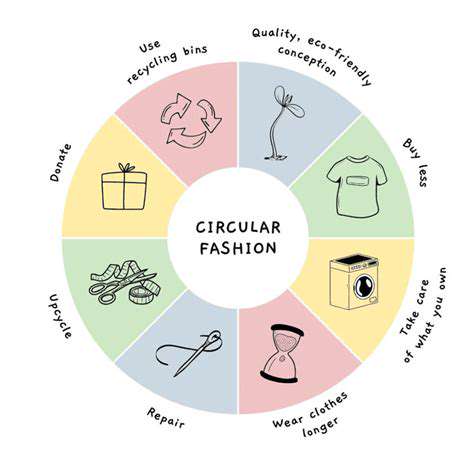

Real progress requires reimagining textiles from molecule to disposal. Designers experiment with closed-loop systems where garments disassemble for recycling, while bioengineers grow fungal-based leather alternatives. Some forward-thinking brands now lease clothing rather than sell it, maintaining ownership to ensure proper end-of-life recycling. Municipalities invest in advanced wastewater treatments using electrostatic precipitation to capture microfibers. These diverse approaches share a common thread—viewing clothing not as waste, but as valuable material in continuous circulation.

The Silent Killer: Impacts on Marine Life

Impacts on Coral Reefs

Reef systems face a slow suffocation under synthetic sediments. Microfibers settling on coral polyps block sunlight and oxygen exchange, while toxic leachates from degrading textiles impair reproduction. Scientists document ghost reefs—once-vibrant ecosystems now draped in fibrous shrouds that prevent larval settlement. The Great Barrier Reef's northern sections show textile fiber concentrations correlating with increased coral disease, suggesting these particles may accelerate reef decline.

Effects on Marine Fauna

From plankton to porpoises, marine organisms suffer from textile ingestion. Filter feeders concentrate microfibers at the base of food chains, while larger animals mistake floating fabrics for prey. Autopsies of sperm whales reveal shocking findings—some specimens contain enough synthetic fibers to fill a laundry basket, with guts so impacted they resemble textile bales. The psychological toll matters too; dolphins entangled in discarded nets show signs of chronic stress comparable to PTSD in humans.

Disruption of Marine Food Webs

Textile pollution reshapes oceanic ecosystems from the bottom up. Microfibers alter the buoyancy and light penetration that phytoplankton depend on, potentially reducing the ocean's carbon-absorbing capacity. When small fish consume fiber-laden plankton, they experience stunted growth and reduced fertility—effects that magnify up the food chain. Some commercial fish stocks now contain so many microfibers that seafood lovers may ingest thousands of synthetic particles annually—an unsettling example of pollution completing the circle back to humans.

The Urgent Need for Collective Action

The Scale of the Problem

Global textile production doubled since 2000, with most growth in synthetic fibers. This surge created a waste tsunami—the equivalent of one garbage truck of textiles lands in landfills or incinerators every second. Less visible but more insidious are the microfibers escaping into waterways—estimated at nearly 2 million tons annually, or the weight of 200 Eiffel Towers worth of synthetic floss polluting aquatic systems each year.

Solutions and Collective Responsibility

Real change demands participation across society. Consumers can adopt the 30 wears test—will I wear this 30 times?—before purchasing. Dryer manufacturers experiment with lint capture systems that prevent microfiber aerosolization. Perhaps most impactful are emerging policies like New York's proposed Responsible Textile Recovery Act, which would make brands financially accountable for garment end-of-life. When paired with textile-to-textile recycling breakthroughs, such measures could finally turn the tide on this crisis.

Economic and Societal Implications

The true cost of cheap fashion becomes apparent in ocean cleanups and healthcare expenses. Economists calculate that microplastic pollution may cost global fisheries up to $15 billion annually in lost catches and damaged equipment—a hidden subsidy for fast fashion paid by coastal communities. Conversely, the circular textile economy could generate millions of green jobs, from sorting technicians to biorecycling specialists. The choice isn't between economy and ecology—it's about building an economic system that values both.